Seattle's Health Care Workers: The Stories Behind the Masks

Jozette Danek and David Danek

Jozette Danek worked on an ICU floor during the coronavirus pandemic. She saw worse than her husband David, a telemetry nurse. “When you have somebody that you know is dying, and you as the nurse are the only one that can hold his hand—to me, that’s the hardest,” says Jozette. David knew his wife of 16 years cared deeply for her patients. It’s why the Swedish Issaquah charge nurses both pursued the profession. But David never quite grasped the depth of her passion until Covid-19 struck. “That was an awakening to me.” He tried to offer her support, and vice versa, but their shared viral exposure also weighed on them. They’re older, at a higher risk than most nurses. They discussed how long they’d want to be on life maintenance. Over time, community support—a Facebook post, a “we love Swedish” message across a bridge—helped raise their spirits. “We’re kind of over that emotional hump,” says David.

Anne Lipke, ICU doctor at multiple Swedish campuses and the director of the Issaquah branch’s ICU during the pandemic. “I am incredibly proud of both our medical response and our community’s response to Covid.” Mark Brumfield, housekeeper in the emergency room at University of Washington Medical Center—Northwest. “I would like to say thank you to the community for all your support.”

Matthew Gockel, clinical social worker at Swedish Issaquah. “Unfortunately, some of my patients don’t make it home. Inequality doesn’t stop, so neither will I.” Brenna Born, emergency department physician and medical director at Swedish Issaquah.

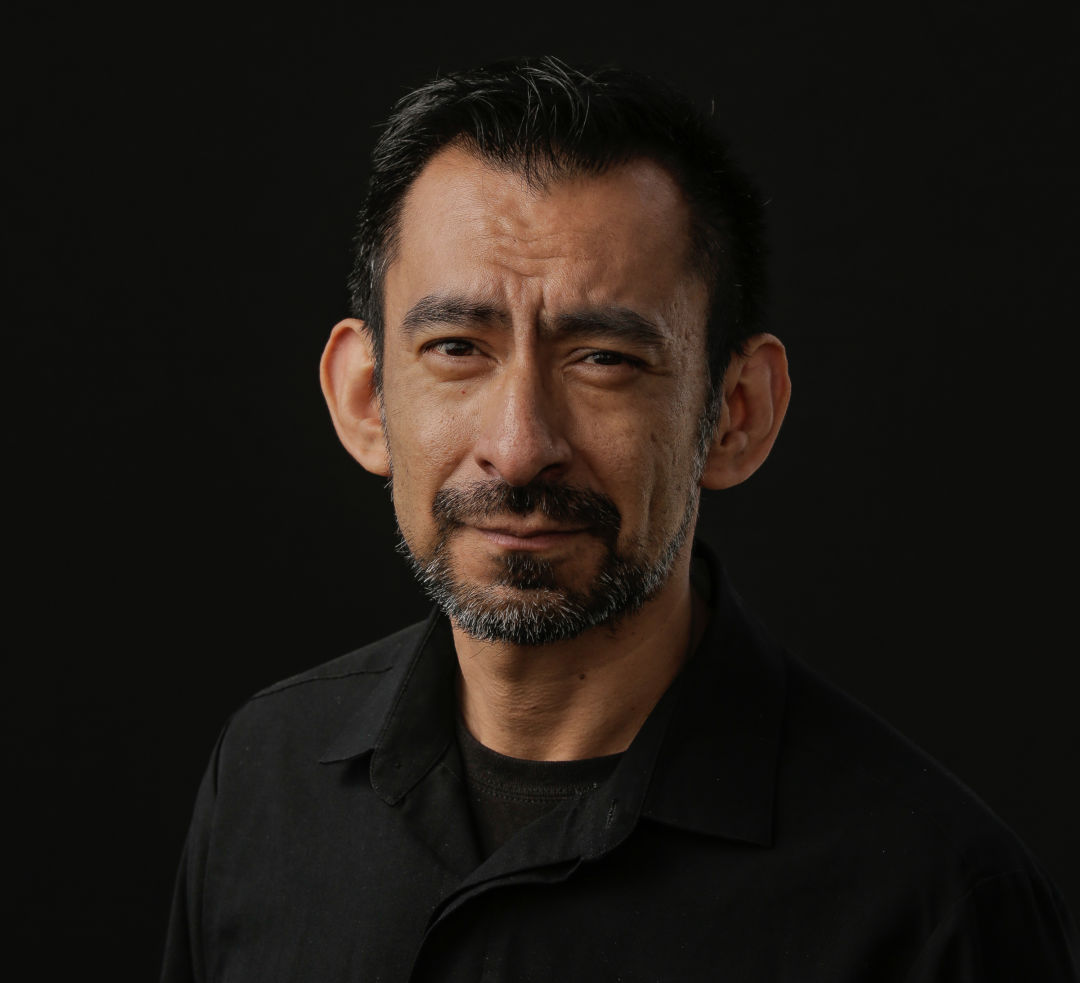

Leo Campa

Leo Campa has seen people in tough shape. As a meal server at Harborview Medical Center since 2009, the West Seattle resident drops off trays for patients who suffer from a variety of serious conditions, such as severe burns. But when he began passing rooms with Covid-19 patients hooked up to ventilators—one of whom was a nurse at the First Hill hospital—the situation scared him. “It feels unreal when you’re up on the floor,” says Campa. “You see how bad it really is.” Still, the grim scenes didn’t deter the nutrition services worker, whose perpetually “sunny disposition” helped earn him a University of Washington Distinguished Staff award in 2014, from delivering puree or solids to patients based on their dietary needs. Nurses consider him part of their team, though that’s nothing new. “He is one of those special people,” nurse manager Tara Lerew wrote back then, “that everyone wants to be around.”

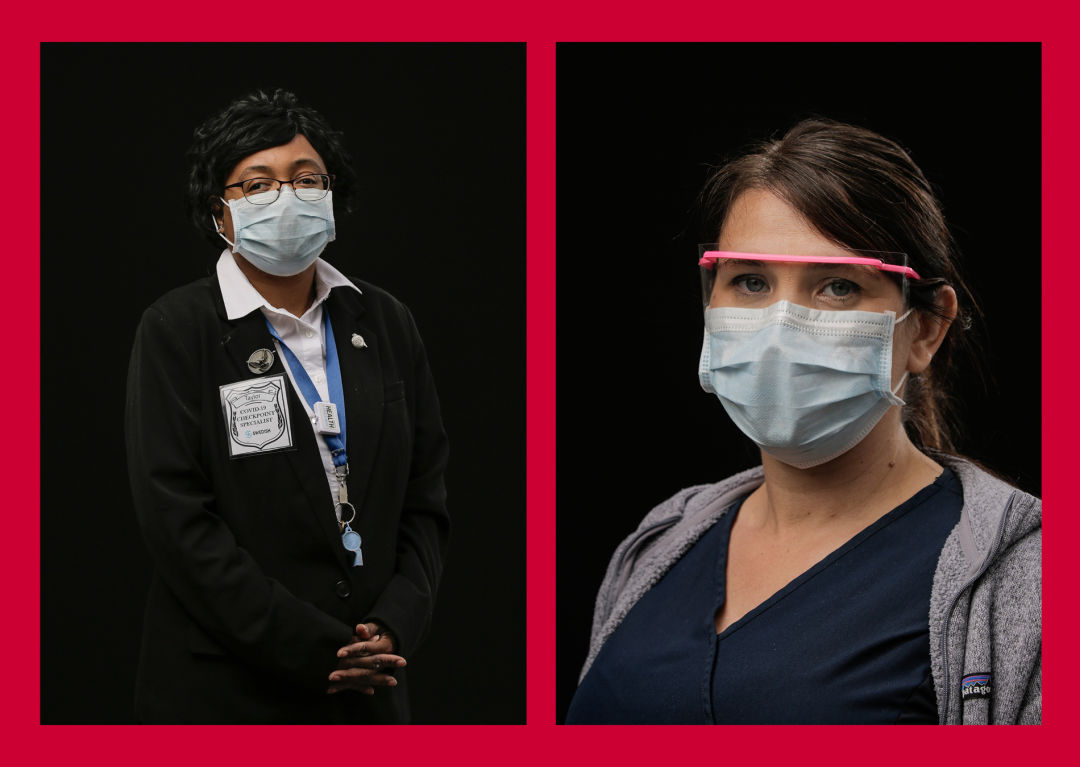

Tallsa Taylor, cashier and visitor screener at Swedish Issaquah. “I have read about big historic moments in the world like World War II, the Great Depression, and 9/11, but I never thought I would experience a historic moment firsthand.” Theresa Novak, nurse who screens employees and patients entering Swedish Issaquah. “Here for all the people.”

Jennifer Hartley

In March, Jennifer Hartley learned that a nursing school friend had died of Covid-19 in California, presumably infected by a patient. “To work in the ICU, you do have to learn some degree of putting things in boxes,” says Hartley, a nurse practitioner at Swedish First Hill. “So, when your worlds collide, that’s really what will bring you to your knees.” The director of critical care nurse practitioners and physician assistants at Swedish still managed to help guide her courageous colleagues through the crisis. She compares her fellow ICU workers to generals, captains, and infantry in the battle against the virus. “They spend countless hours in rooms taking care of patients in the most challenging circumstances. I think their compassion has transcended this disease.” For Hartley, the pandemic has presented a silver lining. It’s allowed her to focus on what’s truly important: “our relationships with people.”

Juanita Willams, environmental services tech at Swedish First Hill. “We will soon overcome.” Casey McGee, materials distribution technician who has worked as the personal protective equipment warehouse tech during the pandemic at Swedish First Hill.

Sophie Miller, internal medicine physician at Harborview Medical Center. Shikha Bharati, nurse practitioner at Harborview Medical Center, monitors the hospital’s own employees for Covid-19 symptoms.

Adrienne Fernandez

Imagine a person sitting on your chest. Now imagine that weight, that pressure, remaining there for days. That’s how Adrienne Fernandez describes the worst portion of her bout with Covid-19, which sent her to the emergency room. “I couldn’t breathe,” she recalls. Ironically, her sickness may have stemmed from the ER. In early March, the then emergency department registration supervisor had checked in patients with coronavirus symptoms to the University of Washington Medical Center—Northwest, including multiple confirmed cases. Fernandez’s own bug started mild enough—a sore throat, a loss of smell—before a fever and chest pain led to a positive test. The Central District resident would recover for a month at home before returning to work, where less fortunate patients needed her help. “It made me more committed to health care,” she says, “and I was so blessed that it didn’t mean my life.”

Maricon Nibre, nurse at Harborview Medical Center who lost six patients to Covid-19 early in the crisis. “I brought six people home, but I held their hand and they held my heart.” Michael Sison, emergency room nurse at Swedish Issaquah.

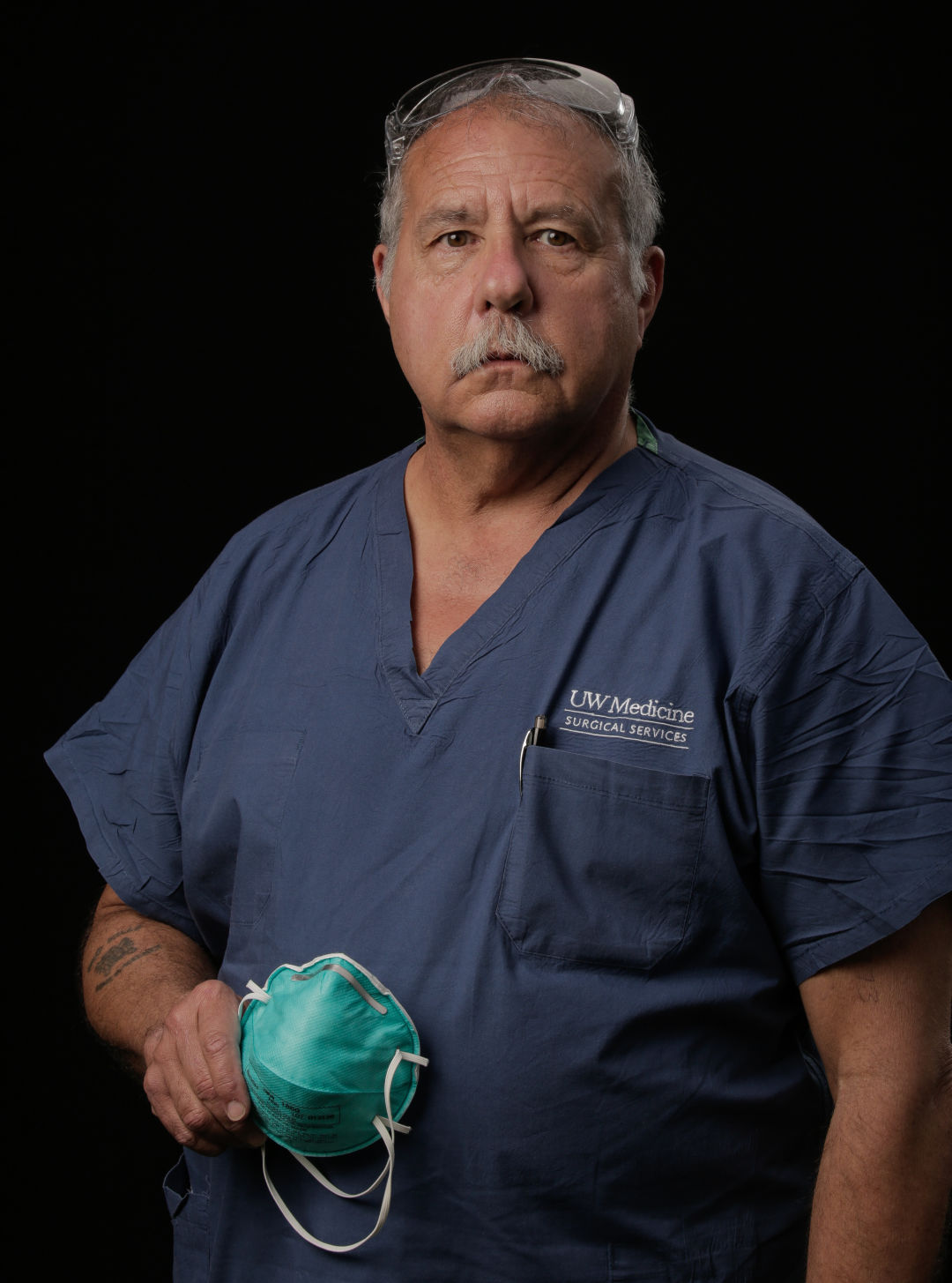

Mavrick Homer

Mavrick Homer had a relaxing spring scheduled. The post-anesthesia care unit nurse and his wife would spend May in an Arizona retirement community, a trial run for a more permanent stay in a couple years. Instead, Homer found himself in the ICU at the UWMC—Northwest, removing personal protective equipment from medical staffers and transporting Covid-19 patients to other areas of the hospital amid a pandemic. Sometimes, the tenor of the work could change just as quickly as his retirement plans. One time he chatted with a jovial elderly patient about Judge Judy as they waited for his test results. He later learned the man was Covid-positive. “If he goes on a ventilator, he is not coming off,” Homer recalls thinking. Other moments brought joy, like watching a man get wheeled out of the ICU to hearty cheers. “I hadn’t been there for his course of his illness, but on the day he got out—we all share in that success of, yeah, people are getting better.”

Joel Castrellon, nurse anesthetist at Harborview Medical Center. Noy Monserate, ER nurse at Swedish First Hill. “Working in the ER is both a scary experience and…a satisfactory experience for me to be able to help those that need it most during this pandemic.”

Brigitte Ebert , nurse at Harborview Medical Center. Vozzie Marshall, operating room assistant at the UWMC—Northwest, quotes James Baldwin: “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

Maureen Acholonu

Though hospitals have never lacked for specialization, the coronavirus pandemic called for a new job, one that was especially precise—and vital. Affectionally dubbed the “dofficer,” a medical staffer helps nurses, doctors, and others safely remove their potentially contaminated personal protective equipment after visiting the rooms of Covid-19 patients. At the UWMC—Northwest, nurse Maureen Acholonu possessed the fastidious eye and order of operations know-how necessary for the job. With ease she rattles off the tedious steps for doffing gear—the disinfectant handoff to wipe down the inner door handle, the simultaneous glove-and-gown removal while facing the patient. But then she details her own doffing routine upon returning to her Edmonds home after shifts. To protect her loved ones, she discards her clothes in the garage and showers downstairs before joining them. Her faith inspires this devotion to her family and her patients. “You know you’re doing what you’re called to do, helping somebody recover.”

Michelle Fero, medical-surgical nurse who updates colleagues on changing policies and best practices for using personal protective equipment at Swedish First Hill. Alex Vengerovsky, ICU physician at the UWMC—Montlake.

Samuel Warby, public safety officer at the UWMC—Montlake. Sherri ThunderHawk, certified nursing assistant at the UWMC—Northwest. “Don’t live in fear, but respect the virus.”

Gretchen Rohrbaugh

As a labor and delivery nurse, Gretchen Rohrbaugh often has to guide families through impossible decisions; not all pregnancies end with balloons and baby blankets. The outset of the coronavirus pandemic, however, presented some unique challenges for Rohrbaugh and others working in the UWMC—Montlake birth center. Most excruciatingly, expectant mothers who’d tested positive for Covid-19 weren’t allowed any visitors during childbirth. Those who tested negative could have just one initially. Try delivering this news: “‘Sorry, your husband can’t come because you chose your mom,’ or vice versa,” says Rohrbaugh. The restrictions compelled more creative forms of support. In one case, an expectant mother’s mom held up supportive signs on the sidewalk below between FaceTime sessions with her daughter. Still, hospital workers like Rohrbaugh understood they had to provide more emotional support than normal. “I would hope that my nurse would show up with as much presence and strength as possible—to be there for me in that time.”

Abubacarr Jobe, biomedical technician in clinical engineering who repairs and maintains medical equipment used on patients at the UWMC—Montlake. Bașak Çoruh, pulmonary and critical care physician at the UWMC—Montlake. “It’s a privilege to care for the sickest patients in our community with Covid-19.”

André Mattus

The decision came down swiftly: Another patient needed intubation. Staff at the UWMC—Montlake scattered, gathering equipment and personnel to hook up another ventilator. André Mattus remained at bedside. The nursing assistant couldn't actively help with the device’s application, so he found another way to offer aid. He sensed the still-conscious Covid-19 patient needed comforting before the procedure, which involves the insertion of a tube down the throat to assist with breathing. He held their hand, listened to words he would later recite to their significant other over the phone. “There wasn’t really much medically I could do, but the least I could do was be a human taking care of another human,” says Mattus. As he embarks this fall on UW’s accelerated bachelor’s in nursing program, Mattus won’t soon forget an experience that no textbook or online video could have simulated. “It’s moments like these that I know will impact the rest of my career as I enter the field of emergency medicine.”