Shaun Scott Chronicles Seattle’s Civic Shortcomings through Sports

For author Shaun Scott, sports became “a secondary political education.”

Last summer, in the run-up to the 2023 MLB All-Star Game in Seattle, city staff swept away homeless encampments that would have been in the vicinity of the gleaming national spectacle. Protesters denounced mayor Bruce Harrell’s administration for its sudden displacement of people in the throes of a housing crisis; pundits noted the administration’s sudden attention to neglected SoDo streets came as tens of thousands were set to visit the region.

City officials portrayed the timing as coincidental—a continuation of its encampment removal policy. But glossing over problems in the name of sports tourism is as much a city hall tradition in Seattle as an outgoing mayor leaving a letter in the desk for their successor. The sweep in 2023 was reminiscent of 1995, when mayor Norm Rice oversaw the arrest of protesters who erected an encampment near the Kingdome before the NCAA Final Four.

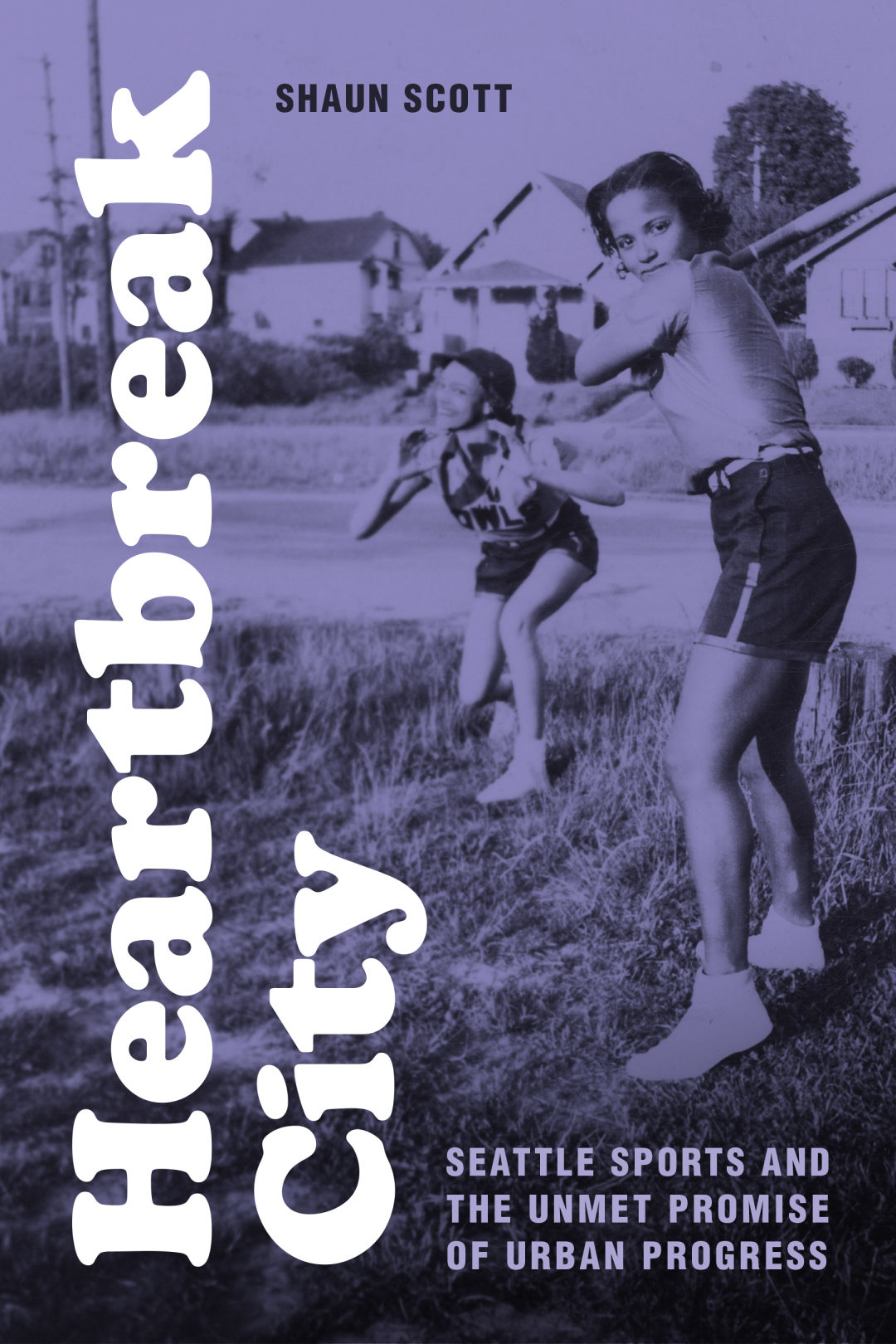

Shaun Scott writes about that incident in Heartbreak City: Seattle Sports and the Unmet Promise of Urban Progress (University of Washington Press), a history that twines the region’s athletic triumphs and setbacks with its turbulent political trajectory and perpetual quest for a big-city pat on the head. “We’re a city that is starved for recognition,” Scott says.

He traces this inferiority complex back to the Northern Pacific Railway’s decision to site a terminal in Tacoma instead of Seattle in the late nineteenth century. Around that time, baseball popped up in the area and started to reflect the growing metro’s character. As Scott demonstrates through accounts of everything from the 1917 hockey champion Seattle Metropolitans to the Sue Bird–era Storm, sporting events allow the city to show its true identity—which might not be as progressive as many would like.

Certainly not for the author, a member of the Democratic Socialists of America who ran for Seattle City Council in 2019. (It was his “leftist diatribes” in print and on social media that led to a manuscript request from a UW Press editor, Scott writes in the book’s acknowledgments.)

The local filmmaker and wide-ranging historian—his last book, Millennials and the Moments That Made Us, focused on pop culture—moved from New York to Seattle in the early 1990s with his father. He quickly fell into the thrall of UW, Sonics, and Seahawks fandom. But in 1995, the same year as that Final Four protest, his view of sports shifted.

Around that time, a talk radio show criticized Sonics guard Kendall Gill for missing games due to depression. Scott’s father was livid with the commentary and called in to express his disappointment. Later, he stressed to his 10-year-old son that athletes were still human. They were laborers, not just sources of entertainment, as media often depicted them. Sports were politically coded, Scott learned. “I…never quite looked at sports and how they were viewed the same way after that conversation.”

This realization didn’t turn him away from the games. Instead, they became more compelling for him, “a secondary political education.”

As he grew up, Scott would probe beyond the jersey-deep reads on the departure of the Sonics, the sometimes icy treatment of Ichiro Suzuki from media, and criticism of outspoken Seahawks. But the sports history that came before his own consciousness—the first seven “innings” of the book—was largely unknown to him before embarking on the project. He relished learning about Coast Salish tribes’ games of shinny (a hockey-like sport played with curved sticks), Helene Madison’s triumphs in the pool at the 1932 Olympics, and the 1987 Seahawks strike that brought athletes and other organized laborers together.

Unlike the place that has played host to these athletes and games, Scott’s book doesn’t shy away from the problems surrounding them. Settlers stole Coast Salish land. Madison faced sexism and had to sell hot dogs in Green Lake Park to provide for herself after winning three gold medals. Racist refs cost Elgin Baylor and Seattle University the 1957–58 men’s basketball championship.

A city’s attitudes can evolve. At the same time, the corporate progressives who “faked left and went right” were the very same forces that led to the Sonics’ departure in 2008.

Sports tourism isn’t going anywhere. On New Year’s Day, the NHL’s Winter Classic will be played at T-Mobile Park. The following year, the NCAA men’s basketball tournament will return to Seattle at Climate Pledge Arena. And in 2026, Lumen Field will host part of men’s soccer’s World Cup.

Scott just hopes that the city learns from its past by, this time, investing more in the community first.

“With that thirst for recognition, I think we’ve done some pretty awful things as far as trying to conceal what the reality of life is here,” he says. “But I think we’ve also been, conversely, at our best as a city when we realize that taking care of residents who are already here pays many more dividends.”