A Seattle Author Traces His Family's Holocaust Survival in Soviet Ukraine

Goldenshteyn drew from his background as a journalist to write and report on a bit of family history he never knew.

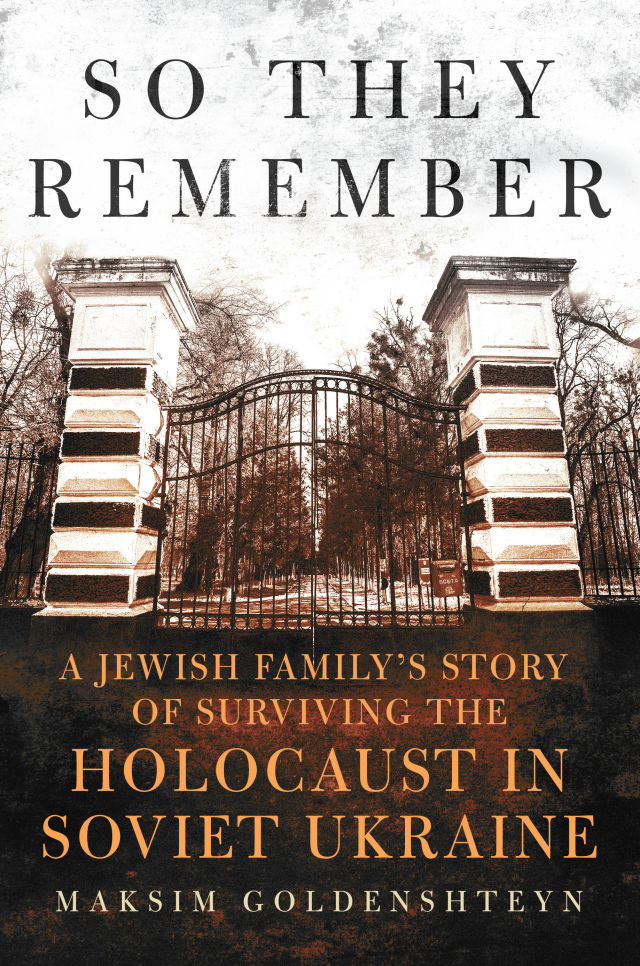

Image: Courtesy Maksim Goldenshteyn

With his young family fast asleep, Maksim Goldenshteyn sat at the dining room table and pressed play.

The recording crackled. A man's voice, his grandfather's, cut through the din.

Nearly five years earlier, in 2012, Motl Braverman plopped down on his couch in Bellevue and relayed the war story he'd long withheld from his scruffy 23-year-old grandson.

In 1941, Braverman and almost every other Jewish resident of Tulchyn, a small town in Soviet Ukraine, were sent to a "death camp" in Pechera started not by German Nazis but by Romanian allies at the urging of dictator Ion Antonescu. For years, like others in these lesser-known camps across Eastern Europe, they battled starvation, disease, and the volatility of relationships upon which their lives depended.

Goldenshteyn, a recovering journalist then working in marketing, leaned on his reporter instincts and recorded their hours-long conversation that Saturday afternoon. Listening back in 2017, one line stuck with him. "You should write this so no one forgets," Braverman said. "So they remember."

The book that arose from this directive details a different kind of concentration camp than what's traditionally depicted in books and movies. "The camp's setting was not an isolated complex found at the end of a rail spur...but the grounds of a former manorial estate in an idyllic village," Goldenshteyn writes in the prologue of So They Remember, published earlier this year. "The story was full of paradoxes: Ukrainians who both saved and tormented Jews; guards who turned a blind eye to escaping prisoners; escapees who returned to the camp time and time again even after managing to flee."

Survival was predicated on social endurance as much as physical; relationships forged with groups outside the camp could lead to more rations and, maybe, liberation. "The Holocaust, in Eastern Europe especially, was a very kind of public event," Goldenshteyn told me by phone Sunday. In one passage, Braverman, who died in 2015, describes a surreal visit to a town beyond the iron gates. "What was happening in the camp? How do people live there? People would come by to see me, as if some alien had descended on them."

The encounter conjures the present, as Ukrainians have fielded questions about the Russian invasion for weeks now as most of the world watches at a distance. Unlike some local families with Ukrainian roots, Goldenshteyn's relationship to what's happening abroad isn't quite so direct. His loved ones are all elsewhere at this point.

It's been three decades since Goldenshteyn himself arrived in the U.S. after spending his earliest years in Chernivtsi, Ukraine. His family settled in Bellevue, where many Russian-speaking refugees in the early 1990s took up refuge. Russian delis and bakeries popped up on the eastern side of town. "It was also where one could spot elderly Russian-speaking men with frayed baseball caps observing chess matches at the Crossroads Shopping Center and where couples dressed in one or two layers too many strolled the parks, waited at bus stops, or walked home along busy arterials with bags full of groceries," Goldenshteyn writes.

Ukraine had only just gained its independence back then. "Most people that were Jewish would have identified, probably, as Russian-speaking Jews or Jews from the former Soviet Union, not so much Ukrainian Jews," he says.

It's a complicated identity. The book details how some Ukrainians collaborated with Germans and Romanians in mass executions and other atrocities during the Holocaust. At the same time, the Hasidic movement took off in the territory.

Goldenshteyn says the Maidan Revolution in 2014 fostered more national pride for him, and the country's response to the "horrifying" recent events have only strengthened it. He's been parading around his North Seattle home, saying "slava Ukraini!" ("glory to Ukraine!") of late, annoying his wife. "Watching a Ukrainian Jewish president capture the imagination of the world—I mean, it's beyond anything we could have imagined."

But Goldenshteyn's book lays bare that we're not so far removed from the unimaginable, which was exacerbated by a public, in part, kept in the dark. Soviet media often ignored the plight of those in the camps, and it would take the Romanian government nearly 60 years to acknowledge its role in the deaths of at least 400,000 Romanian and Ukrainian Jews. There was a broad "policy of forgetting."

Today, Ukrainians face a similar barrier. Some of their relatives in Russia don't believe there's a war happening. "I think that really highlights the importance of ensuring that history is told and documented in the right ways," says Goldenshteyn, "because otherwise, it's really quite easy for leaders to paint a picture that is completely inaccurate."

As he knows all too well, you can't remember what you never knew.