The Ancient Spirit That Settled in Small-Town Washington

The golden god first appeared in suburban Washington in 1977.

Let’s put aside for the moment whether Ramtha is best described as a god, or the God—or a ghost, or an alien, or a total fiction. According to legend, he appeared to 30-year-old JZ Knight in her Lakewood kitchen as an apparition of golden glitter in a haze of blue aura. He stood seven feet tall, clad in a robe of purple and white and pure light, in the same room her two young boys had left crusty cereal bowls and the remains of peanut butter toast.

Nearly half a century later, Knight has built upon that initial encounter to fashion herself a New Age mogul, a spiritualist who drew an Oscar winner and a Dynasty star to her orbit, a figure of mystery. The being she calls Ramtha enters her body and speaks with her voice to dispense mystical wisdom to rapt students of her Ramtha’s School of Enlightenment. Visitors come to her compound in Yelm, some 60 miles south of Seattle, ringed by low walls and a curlicued iron gate, to seek a glimpse behind the curtain of the universe and perhaps at the audacity of power over our own existence.

Knight’s vision—or, depending on whom you ask, willingness to play host to this foreign entity—has reshaped a small town that has grown accustomed to the unlikely god next door. In the 1970s less than 1,000 people lived in Yelm, a nearly literal one-stoplight town 20 miles east of Olympia. Rust mottled the downtown water tower, and a sign hung on the high school’s chain link fence to prohibit horseback riding on the ball fields. A veritable John Mellencamp song, Pacific Northwest style.

Still, when a patron overhears me say Knight’s name in a dive bar in nearby Olympia, he interrupts to share a sharp “Fuck Ramtha.” Both great loyalty and strong distaste come in equal measure.

And yet Knight herself remains elusive, settling into semi-retirement and declining most interview requests, including ours. Ramtha’s sprawling philosophy is either a life-changing ethos or a local oddity, one that can feel like a cocktail party curio run amok while also encompassing the lives of thousands.

Is Ramtha’s School of Enlightenment a cult? A religion? Harmless woo-woo, or the forefront of metaphysical thought? Is JZ Knight faking the fact that she channels the spirit of a paleolithic warrior—and does that really matter?

A sign along Yelm Highway marks the entrance to RSE.

Be it foreshadowing or coincidence, JZ Knight was born Judith Darlene Hampton outside Roswell, New Mexico, in 1946, a little more than a year before that desert town spawned its infamous UFO tale. For the rest of her life, Knight would fill her orbit with extraterrestrial encounters, from spotting a flying saucer at a teenage sleepover to authoring whole Ramtha volumes about alien civilizations.

Young Judy’s childhood was anything but a sci-fi lark, marked by the grinding poverty of cotton field laborers and her mother’s series of abusive, alcoholic husbands. In her autobiography, A State of Mind: My Story, Knight clearheadedly recounts the sting of being labeled “poor white trash” and the abject horror of being raped by an uncle when she was only four.

Headstrong and faithful, a preteen Knight taught ad hoc Bible lessons to her peers, then bristled at the fire and brimstone talk—the sin and repentance stuff—of her evangelical church. She recalls announcing “I love my own good God” when she left the church. Emphasis on the “good.”

A blond beauty by her late teens, she married young and had two sons; she’d divorce and remarry several times before her last husband gave her the surname Knight. She writes about her youth in proud terms, a midcentury woman left to her own devices to understand love, self-reliance, and sexuality in the wake of early trauma. She’s also pretty sure she is the reincarnation of the half-sister that died as a toddler, a decade before Knight was born.

Knight recalls how her first husband and his pushy mother bullied her into dyeing her eye-catching hair a dull black, leaving her two-toned as it grew out. Spurred by later friendly workplace teasing of her wardrobe, she adopted the nickname Zebra, eventually shortening it to just JZ, no periods.

Though lacking a college degree, the single mother molded her savvy business sense into an executive career in the burgeoning cable television industry, eventually landing in the South Sound in the 1970s. The decade featured, among other things, a trendy fixation with pyramids—from Steve Martin goofing on “King Tut” to the Toronto Maple Leafs using plastic pyramid “vibrations” to hex their rivals in the 1976 Stanley Cup semifinals.

When JZ, intrigued by their purported power, built pyramids out of construction paper in her kitchen, voila. Ramtha appeared, she writes—all seven ethereal feet of him.

The story of Ramtha that Knight shares in her own biography and various Ramtha-authored texts goes like this: The being that speaks through her was a mortal man 35,000 years ago, a warrior who conquered much of the world but hailed from a land called Lemuria. Instead of dying, he ascended beyond the mortal plane to join a collection of A-list masters that includes Jesus, Mohammed, and Buddha; the religion of Knight’s youth has its place in Ramtha’s model of the world.

When Ramtha takes over her body, per Knight, he controls the speech, the movement, the message. She in turn parlays that wisdom into thousands of pages, dozens of books, hours of DVDs. Ramtha’s general philosophy reflects can-do self-empowerment—one intro text is titled A Beginner’s Guide to Creating Reality—with a hearty splash of UFO-logy and what a layperson might call magic. Ramtha is not God, exactly, but rather evidence that humans are all aspects of the being we call God.

Ramtha’s narrative weaves through the historical tenets of occultism and spiritualism, if not the historic record: Anthropologists record no global conquest in the late Paleolithic. His hometown, that lost continent of Lemuria (not Atlantis, but same

vibe), was popularized by the nineteenth century’s trendy Theosophy, a mystical movement all the rage in an era when attending a séance passed for a night on the town. The 1980s version of this was Knight, as Ramtha, channeling in person during presentations in hotel ballrooms, a world tour for an otherworldly being.

Ramtha’s circle grew, extended to Hollywood. In a memoir, the famously spiritual actress Shirley MacLaine called her relationship with Ramtha “deep, seeming to speak to another time and place.” Airline executive Steve Klein read those words in the Tucson, Arizona, airport, having picked up the book en route to Thanksgiving 1985. Raised Jewish, Klein felt an awareness of having past lives. He sought videos of Knight’s channeling on VHS, then made his way to Phoenix’s Ramada Inn, already sure he recognized the being. “This is my frequency,” he says today.

Soon, Klein was attending Knight’s presentations around the world, sharing insight with her staff about optimizing business travel to earn mileage rewards. He was eventually hired to work in community outreach for the school; though still a student, he has since retired and no longer represents the school.

In her trance state, Knight-as-Ramtha holds court, equal parts wise and wisecracking. This personality appears to be a jokester as much as a philosopher; as Ramtha, the short blond Knight strides around and manspreads with masculine gusto. Like the cliched professor pontificating by a fire, he—she—even smokes a tobacco pipe.

Even as he descended to enrich the masses, Knight says Ramtha helped her access more past lives. The woman once abandoned and abused by fathers, stepfathers, and ex-husbands wrote that she retrieved memories of being Ramtha’s beloved and headstrong daughter in his original world-conquering lifetime.

Ramtha is supposedly all-powerful, ageless, on a dimension beyond humanity. So why does he need a Washington mom of two? Because, Klein maintains, Ramtha isn’t a religion. “He is not going to give us the opportunity to corrupt his message by having us focus on an image of him.” Klein considers Ramtha an ideal—he spells out each letter for emphasis—not an idol.

“This is that which is called television?” A 40-something Knight speaks in an almost cartoonish cadence, leaning back to peer under her blond bangs, fluffed to era-appropriate heights. Her gaze meets the bemused face of Merv Griffin on the set of his eponymous talk show in late 1985. Here’s Knight, channeling Ramtha in front of network TV cameras, as a crowd erupts in the familiar cheers of live-in-front-of-a-studio-audience television. Knight, as Ramtha, bows and kisses Griffin’s hand.

“You’re my first 35,000-year-old guest,” the host says, jovially playing along. Knight—or Ramtha—displays the slight purr and off-kilter diction that marks Ramtha-speak. “You are well this day, in your time?” This being the mid-1980s, Griffin asks for a prediction, if the planet is headed for a nuclear holocaust.

“The earth will never be destroyed…it will go on and on,” Ramtha assures him, but claims a greater consciousness is coming. Griffin responds with flippant remarks, and the audience roars again.

But not everyone was a fan. In 1988, staffers at her school say, death threats at an event in Colorado drove Knight and her students back to her Yelm residence. They finished that retreat in her home’s stately riding arena, on a floor scattered with wood chips. Knight went on to establish a permanent school in the horse ranch so pupils could come to Ramtha instead of the other way around.

“Science explains God here,” says Debbie Christie as we walk the hallway of a building once home to Knight’s prized Arabian horses. The school took over a stable topped with glass cupolas and bordered by tidy white fencerows, a patrician style more suited to Kentucky’s top thoroughbreds than Thurston County’s workaday farming.

Outside, a gate slams shut abruptly without anyone touching it; most of us would blame a rare gust of August wind, if we noticed it at all. Christie releases a quick smile and says, into the empty air, “Hiya, Ram.” Ramtha explains all things here—more than even science.

The 61-year-old Christie walks the fields in a school T-shirt and shorts, her unfussy, shaggy hair catching the same breeze. She speaks of Ramtha the way one would a beloved boss. Though only Knight (and occasionally her romantic partners) sees Ramtha, his students say they sense him all the time.

Christie was just 24 when she moved from Arkansas to learn from Ramtha; now she is one of only four teachers at Ramtha’s School of Enlightenment. Four, that is, besides the big guy himself. When she arrived in Yelm, Christie helped clear rocks from Knight’s new 80-acre property. Halfway between the still-modest capital city and Mount Rainier, past an Indian reservation that hadn’t yet built a casino, this stretch of Thurston County was squarely rural and sparsely populated. The horse-loving Knights—JZ had married yet again—built the ranch of their dreams.

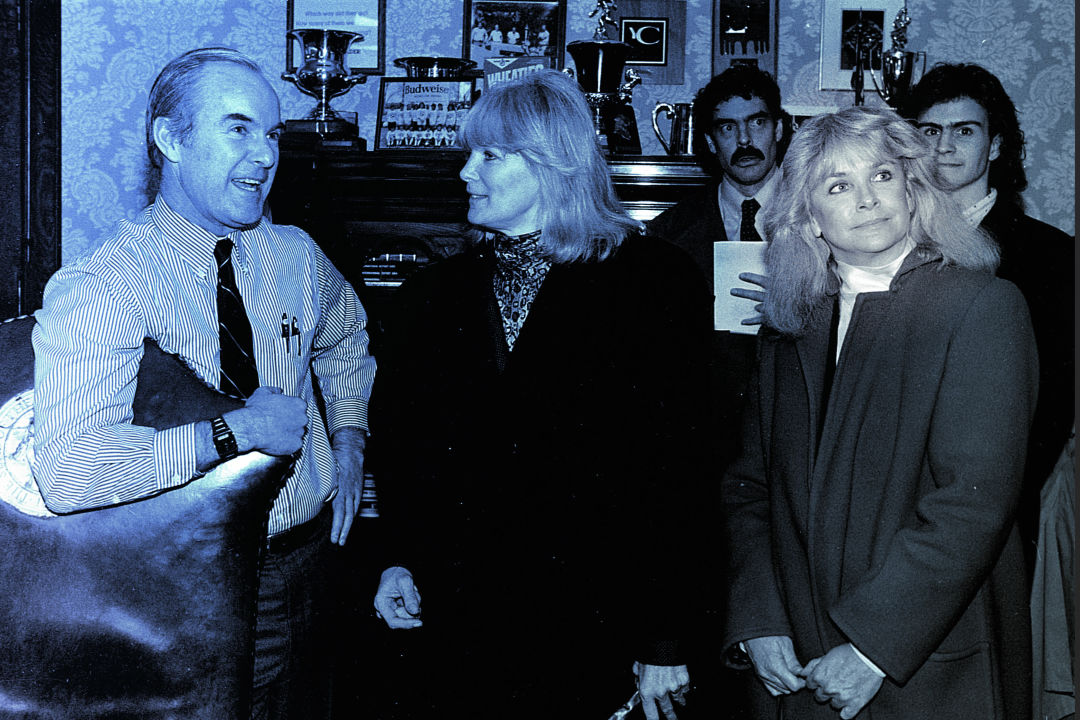

JZ Knight (far right) with Dynasty actor Linda Evans and governor Booth Gardner in February 1989.

During the 1989 remodel that turned the stalls and breeding facilities into offices, the riding ring became Ramtha’s cavernous auditorium. It’s decorated with symbols and banners, on one end a reproduction of Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam fresco from the Sistine Chapel next to the blue figure of Hindu god Shiva. Diagrams outline seven sections of the light spectrum: not just X-ray and infrared, but the “infinite unknown” out past gamma rays. A painting of Knight proclaims “You can do anything. The key is focus!”

Taped rectangles on the Astro-Turf floor, each big enough for one yoga mat, surround the stage where Knight-as-Ramtha appears. On the opposite wall, a Nike “Just Do It!” banner hangs over the booth where Christie—who serves as the sound engineer—records every lecture. From her vantage point in here, Christie says she can catch a glimpse of a seven-foot shadow when Ramtha controls Knight’s body.

Ramtha usually inhabits Knight before entering the auditorium, then may lecture for hours, seated in the middle or pacing around the stage. Tables for simultaneous translators line one wall, ready to render Ramtha’s words immediately into French, Italian, Chinese, German, up to 13 other languages for the international audience. Before the pandemic as many as 850 students could fit in the space, though for the past two years most of Ramtha’s lessons have been streamed virtually. The gender split among students favors women.

Beginning students undergo a six-day retreat here, camping on the lawns or even sleeping on yoga mats in the auditorium. Pre-pandemic, prices ranged around $450 each; Class 101 online now runs $720 and a recent one-day lecture from Ramtha cost just $150. Besides hearing from Ramtha, attendees do mental exercises meant to strengthen the mind toward clairvoyance. A teacher hides a picture of an object, and students sketch what they sense, a cat or a tree or a glass of wine.

Training continues outdoors, in fields ringed by white fences. Blindfolded students try to focus their way toward a specific index card, taped at random somewhere on a fencepost. “It’s about the manifestation and the journey,” explains Christie. "You’re moving to your destiny.” The fields abut Knight’s private home, a sprawling white mansion hugged by now-towering evergreens.

Staff watch from above as blindfolded students navigate a maze, another core exercise meant to teach students focus of the mind, not of the eyes. On another patch of grass, archery: Students gently pull arrows onto a bow, their vision obscured by sleep masks and bandannas, to hit the bull’s-eye without the aid of sight.

Ramtha’s lessons are sweeping and multitudinous, many of them trademarked. (The United States Copyright Office lists 1,015 entries for Ramtha in its public catalog.) One theme emerges, that human consciousness and energy create reality—a kind of DIY ultimate power. It’s not about worshiping a god, but being one. Doodling a cat or hitting a bull’s-eye is only the first step; students test their newfound focus at local reservation casinos, trying to manifest a slot machine win, or on scratch tickets.

The trick, says Christie ruefully, is not focusing on the effort: “When you’re trying you’re not in a pure state of mind.” Or as Yoda put it a few years after Ramtha appeared, there is no try. Once expectation sets in, the winning stops—hence Christie’s personal uneven casino success.

When Christie first moved to town, so few cars came down Yelm Highway that she and her friends would play tennis in the road. Today, 36 years later, her whole social circle is Knight’s school. She visits her family in Arkansas—or did before the pandemic—but struggles to connect with her father, who doesn’t want to hear about the entity around which her life revolves. “Maybe he thinks it is a cult,” she says.

Yelm has grown beyond its rural roots thanks to nearby Joint Base Lewis-McChord—and Ramtha’s School.

The word hangs heavy over Ramtha’s School of Enlightenment. Over Knight. Over Yelm. “‘Cult’ is a dirty little four-letter word that people use when they don’t like something,” says Steve Klein, the former staffer, who still considers himself a student.

Critics bandy the label around online, including in an article from the Southern Poverty Law Center. It surfaces on Enlighten Me Free, a website founded by former student David McCarthy, critical of Ramtha. There forums track the school’s legal doings and record complaints about the organization, of people who feel tricked and misled. South Sound pastor Jeff Adams, now a corrections chaplain and mentor to critical former students, called it “our local cult” in his Nisqually Valley News column.

Anthony Stahelski, a Central Washington University lecturer of psychology, hadn’t heard of RSE in his studies on cults. When he takes a cursory glance at the school, he says, he does see red flags. “They generally feature a strong degree of in-group, out-group, us-versus-them” thinking, he says. Most cult leaders have charisma, a word that comes from the Greek for “divine light,” and purported special powers.

But, Stahelski points out, RSE members don’t live communally, which lends more credence to its status as an educational institution. In the 1960s and 1970s, a boom in Asian immigration—reverberations of the end of the Asian Exclusion act—did lead to a rise in groups tied to Indian and far Eastern religions, as youth culture grasped at new spiritual paths. He thinks RSE could fit in that tradition.

Defining a cult isn’t simple. “There’s elements of cult-like thinking everywhere,” Stahelski says. He cites consensus that Scientology, a newer and controversial religion, is a cult. But we also use the word for everything from people passionate about iPhone releases to off-the-grid separatists. “Was Jesus a charismatic cult leader?” Stahelski ponders. “Yes, one could say that.”

Before he became the mayor of Yelm, JW Foster had visited the RSE campus as a paramedic, attending to students who’d overdone it on red wine. He’s heard this practice is called the wine purge, though the school just describes it as simply drinking the only mind-altering substance it allows. The school, Foster says, was quick to call for help and friendly to the emergency services.

“She was a figure then of mystery and suspicion…behind those gated walls,” says Foster, whose five-year tenure as mayor ended in 2021. “A lot of it was blown out of proportion.” Students from around the world moved to town, bought homes, opened businesses. If you heard a foreign accent at the Safeway, says Foster, you assumed they went to RSE. Plus, he’d heard, at one point Yelm’s state-controlled liquor store had the highest sales of red wine in Washington.

Yelm has as many churches as any rural Washington town, with Methodists and Baptists and Pentecostals and Mormons. But on the fringe of progressive Puget Sound, just east of a capital city full of grunge and Evergreen State College’s alt-everything ethos, a quirky collective feels less out of place than a megachurch.

Knight funded scholarships for local high school students and was known for substantial donations to local political candidates, most of them Democrats. As mayor, Foster met her at a community event and found her charming. “She doesn’t dress in, you know, flowing robes and ride a broomstick,” he says. The community’s general response to RSE, he says, was “Everybody’s got their own thing.”

Christie says religious protesters picketed outside the school during the ’90s in the midst of the Satanic Panic. The school doesn’t have a dark side, she says, and worship, of Satan or anyone else, isn’t prescribed. In 1986, Knight told The New York Times, “I’m not their leader. I’m not a guru…I’m not somebody’s savior. This is a business.”

Ramtha may purport to exist on a different plane, but the school is firmly tethered to the prosaic world of the legal system. Knight defends her intellectual property rigorously. Before students enroll they must sign a legal agreement not to share Ramtha’s lectures or messages. In 2008 the school sued a life coach in nearby Lacey for co-opting school teachings.

In 1992, in the course of divorce settlement proceedings, JZ Knight’s soon-to-be ex-husband, Jeffrey Knight, raised the specter of cults again. In rebuttal, her lawyer called in J. Gordon Melton, a Northwestern University PhD and founder of Institute for the Study of American Religion, to testify. On the stand, he linked RSE to the Western esoteric tradition, more of a questioning philosophy—and noted that while the concept of brainwashing had been popular at the end of the Cold War, major academia had declared it pseudoscience. Ramtha, he concluded, wasn’t a cult.

Still, Melton was so fascinated by Knight and her school that he visited several times, eventually writing a book about RSE. The students, he says, were not the young adults he saw flocking to the Moonies or the Hare Krishna. “These were people facing a midlife crisis,” he says. “They were coming there to find a new direction.” Coming out of the New Age tradition, they “already believed in yoga, astrology, UFOs, and tarot cards and the like.”

Cults, says Melton, provide beliefs in an authoritarian manner. In an esoteric group, believers can test the teachings. “If they work for you, they will become real to you.” While he saw some students leave and accuse JZ of being a fake, he never saw major evidence of abuse.

In the 1990s, Ramtha still hovered just outside America’s cultural mainstream. Knight had celebrity adherents—the Ramtha-curious would include Dynasty glam queen Linda Evans, Salma Hayek, even novelist Michael Crichton—plus her own 500-page memoir (from JZK Publishing, a division of JZK, Inc.). At its height the school claimed more than 10,000 students. Back then, she and the school still engaged outward, to science and popular culture. And researchers, at least in some quarters, took Knight seriously enough to study her transformation into an ancient warrior spirit.

Melton connected the group to Stanley Krippner, a parapsychology researcher on states of consciousness and hypnosis who similarly held a PhD from Northwestern. He studied fringe subjects, with mainstream academic credentials anchoring him to legitimate science. Like many of Knight’s skeptics, “I had dismissed it as crazy, thinking that she was a faker,” Krippner says today.

Krippner came to RSE in 1996 to study Knight during her channeling sessions. He performed psychological tests to measure her dissociation, then attached electrodes to measure her skin temperature, muscle tension, and brainwaves as she began to speak as Ramtha. The latter didn’t work—she moved around too much as the warrior spirit to get any brain readings, Krippner says. But he saw notable changes in the skin and muscle tests.

“This was something we don’t think can be faked,” he says. “It indicated that she was going into some altered state of consciousness.” While the school’s very foundation rested on a 35,000-year-old man’s spirit, Krippner saw proof of the supernatural from Knight’s own physical body.

He wrote up the study and presented the paper at the Parapsychological Association Conference, but never saw the work get the follow-up or citations he thought it deserved from academia at large. “They think she’s running a cult. I disagree with that,” he says. “There’s a prejudice against people who are using these gifts for financial gain.”

Today Krippner just turned 90, still taking Zoom calls about his research, giving responses at top volume. He insists that scientific study of consciousness is only in its infancy.

Krippner’s science found whole-hearted embrace at RSE. In 1997, the school hosted a conference of psychologists and psychiatrists and sociologists—and press. Newspaper clippings from The Olympian that read “Ramtha seer isn’t fraud” are now framed on the wall of the auditorium. But a little more than a decade later, outside attention would dramatically discredit, rather than elevate, the school.

The RSE gate offers the only glimpse most Yelm locals get of the school.

Ramtha was into streaming before it was cool. Since shortly after Knight began channeling, Ramtha’s teachings have been recorded and archived; Debbie Christie estimates the school has more than 30,000 hours of him speaking. But in 2012, a leaked video of Knight speaking as Ramtha cratered public perception.

Former students released filmed snippets of Ramtha making racist and anti-Semitic statements during a lecture, widely reported as including “Mexicans who just breed like rabbits” and saying Jews had “earned enough cash to have paid their way out of the [expletive] gas chambers by now.” McCarthy, he of the anti-Ramtha website, was one of the distributors.

The school sued to keep the videos from circulating (and won), claiming the comments were edited and taken out of context. But local politicians quickly returned donations from Knight. Even the state Democratic Party passed along its take.

At one time, Knight had contributed to Barack Obama’s presidential campaign, but in the wake of the leak, things shifted. Considerably. In 2016 the school released a video of Ramtha praising newly elected President Trump; it also referenced UFOs heralding his rise to power. During the pandemic a giant Q briefly appeared on the school’s gate, and online blogs claim that Knight “teams up” with the conspiracy theory movement QAnon.

The gate now has a printed sign denouncing vaccination mandates: “Asking about the vaccination status of anyone on this property will be met with civil litigation…now get off my property.”

Mike Wright, another teacher and RSE legal affairs manager, says that the school itself doesn’t have politics, and that Knight’s personal beliefs are just that. Teachings may include self cures, he says—Knight also runs a company operating spa-like blue-light rooms for healing—but he says the school doesn’t eschew doctors. “Ramtha says if you can’t manifest a loaf of bread in your hand, you should keep taking medicine.”

Ramtha appears less these days, the school hosts fewer events, and the 76-year-old Knight is in semi-retirement. Ramtha’s School of Enlightenment has announced she will have no successor, no alternate channel for Ramtha. After her death, those thousands of hours of recorded teachings will underpin the school’s continued educational mission.

Outside its gate, Yelm doesn’t feel quite so provincial anymore, no longer a get-out-while-you’re-young kind of place. Its population topped 10,000 in 2020, also buoyed by its proximity to the booming Joint Base Lewis-McChord. Ex-mayor Foster proudly notes how many local physicians graduated from Yelm High School, and downtown claims both a pho joint and a gastropub. Even Ramtha’s stretch of Yelm Highway swelled when the Wat Prachum Raingsey Buddhist Association built a stupa across the street, the temple’s gold-toned carvings and ornate sculpture a strange mirror to RSE’s campus. Somehow, in one of the least religious states west of the Mississippi, Ramtha’s grandiose blend of self-help and the supernatural wove itself into the rural Washington landscape.

But undeniably, more than 60 years after she claimed her “own good God,” a poor field worker’s daughter from New Mexico mustered the power to radically remake her own life, her own fortunes, the very ground she lives on. She led others to shape their lives into a quest for godlike existence. But that power, as it turns out, is profoundly human.