Jon Mooallem’s New Book Finds Beauty in Being Ugly

In his new collection, Mooallem includes writings about a pigeon-breeding Ponzi scheme in Canada and how an escaped monkey in Florida is indicative of our political climate.

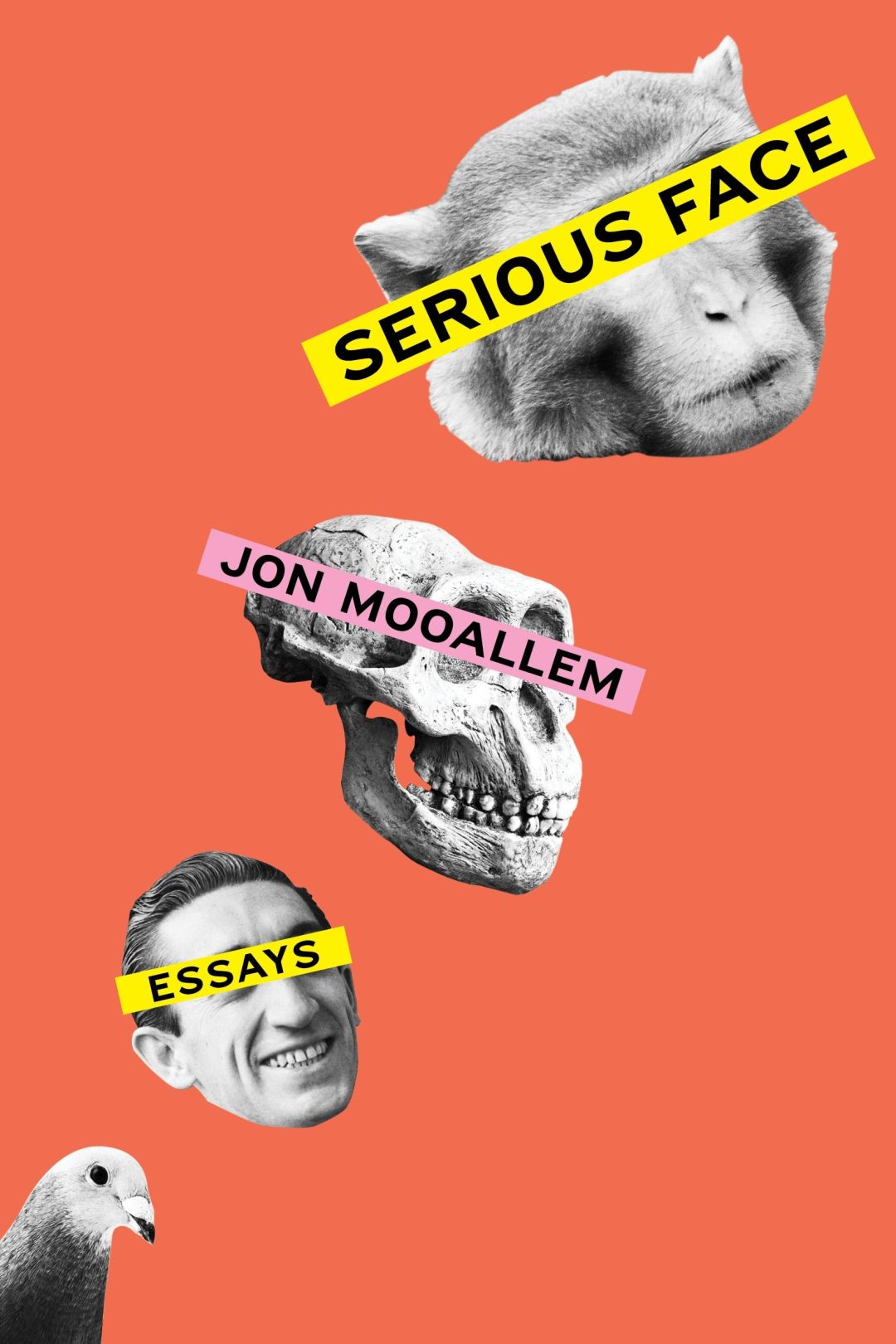

“Island problems,” sighs Jon Mooallem, as we behold the shuttered coffee counter at Town and Country Market, just down the way from the ferry terminal in Eagle Harbor. It’s a May afternoon, the weather teetering coyly between pleasant and chilly, and Mooallem’s third book is coming out today. Serious Face is a collection of essays written mostly for New York Times Magazine, where he has been a regular contributor since 2006.

Our bid for hot beverages foiled, we grab kombuchas and proceed down a sloping sidewalk toward the shoreline, chatting about the “hashtag Island Life,” as Mooallem referred to it archly in a text earlier that day. Bainbridge is, by his own account, a strange place for the New Jersey–born writer to have landed after years in New York and San Francisco. He still sees himself as a city person, in certain lighting—perhaps especially that of a Tuesday at 4:30, when pretty much everything is closed.

How people end up where they are, and why, is at the heart of much of Mooallem’s writing. In assembling this collection, he felt he was taking a retrospective look at his own life, “like I was dead or something.” And revisiting the most significant pieces in his dossier led him to realize he had a preoccupation with “things that don't work out perfectly.”

The title essay from the collection, “This Is My Serious Face” (originally published as “The Matador and Me: Coming to Terms With My Famously Ugly Lookalike”) is a rare turn inward. “My face is a conversation piece,” Mooallem writes, going on to describe, later in the essay, the almost gleeful attachment he has formed to his visage over the years. This despite—or perhaps because of—the “uncontrollable gusto” with which health care professionals suggest everything from rhinoplasty to breaking his jaw to “fix” a face that Mooallem calls “conspicuously crooked,” and which has been described in far less polite terms, especially in his high school years.

The face that launched a thousand dentists into enthusiastic monologues.

Image: Julie Caine

In his introduction, Mooallem crystallizes his fascination with imperfection into a line from an Eric Tretheway poem: “Why are we not better than we are?” The answer is, in every case, that there is no satisfactory explanation. There is no story—no true story, in any case—that can quench our thirst for the sensical. Life, Serious Face will unequivocally inform you, just doesn’t make sense, much as we might poke and prod and massage it in vain attempts to yield some coherent shape. But Mooallem, with clear-eyed generosity, manages to make it something better: meaningful.

The man who unflinchingly chronicles his ugliness for the world (and, to be honest, is perfectly nice looking in real life) answered a few questions about his book.

What themes kept emerging for you, as you looked at these works side by side?

When you spend enough time with someone, and you’re paying close and empathetic attention to them, you realize that—and I don't mean this as a criticism—a lot of us really don't have it figured out as much as we may think we do. We just kind of go through life and we're assembling all this chaotic stuff that happens into some kind of storyline. And I think that's natural and helpful and maybe necessary. But when you actually look at it very closely—and I think it's especially easy to do that when you're looking at someone else—you realize, oh, it's not actually so cohesive and efficient, and we're all spun around in ways that we don't always understand.

You portray people with such generosity in all these stories.

I don't claim to be that magnanimous about it. I think some of it is, honestly, a kind of insecurity. Like, here I am. I'm gonna write about you, and whatever it is you're doing. And I'm not trying to consciously connect with our shared humanity, you know? I just don't want to be a jerk.

The monk seals story [“Can You Even Believe This Is Happening: A Monk Seal Murder Mystery”] is the perfect example. It's basically a story where all of these different factions are looking at this one animal and coming up with different stories about it. And then go to war with each other over it. It's very hard to go into a situation like that and pick who the bad guys are, right? And just be the hammer for all their blind spots. Because you see that everyone's just got this one piece of the puzzle. When you can see life in that way, you realize it's really a smart tactic to just try to be kind.

That story in particular takes the reader on this journey of confronting their own assumptions.

Yeah, and it's funny because I was talking to someone else about the Paradise Fire story [“We Have Fire Everywhere”], and it’s the same kind of thing. The woman at the center of that story, Tamra, was not equipped to deal with that situation. And I think a lot of people could look at that as a story about how we’re not ready for these kinds of natural disasters. But it's also just like, well, that seems like a very valid human response in the grand sweep of how people can react to certain catastrophes.

In “The Outsiders” you follow a man, Dale Hammock, who’s just been released into the outside world after a 30-year prison sentence. What was it like reporting on that?

Well, just to be there when someone gets out of prison after more than two decades is a very exciting, rare thing. You feel an electricity there. And as the day unfolded, it just was clear to me that all the really important things were so small. Like, is he going to be intimidated when they take him in front of the deodorant selection at Target?

You really make the mundane details of everyday life feel alien and absurd, like they are for this man who’s just been released from prison.

My favorite moment is when I’m describing everything that’s on the table at a Denny’s. And there’s a bottle of ketchup that says "Up for a Game?" [The paragraph describes the paraphernalia crowding a diner table, including hot sauces, sweeteners, and a bottle of Trivial Pursuit–themed Heinz ketchup, the preposterous offspring of some ad partnership.]

The world is packed full of so much stuff. And we don’t even notice it.

And none of it makes sense! I think the most heartbreaking thing about Dale was that he thought all this was supposed to make sense.

As told to Sophie Grossman. Transcript edited for length and clarity.