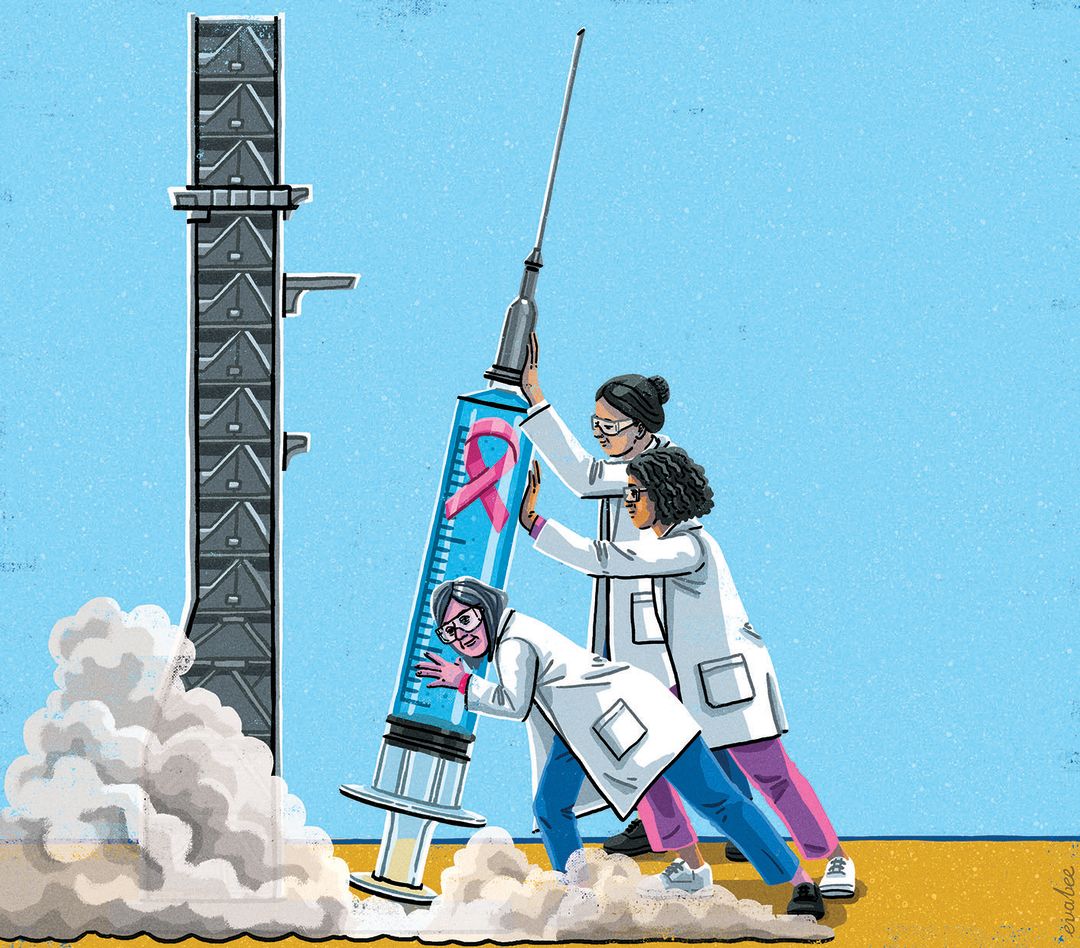

Are We on the Cusp of a Breast Cancer Vaccine?

Image: Eva Bee

Classic sexism propelled Dr. Nora Disis into breast cancer research. “I was the only woman in my oncology fellowship class, so they had me attend the breast cancer clinic.” The old boys’ club gets a pass this time because Disis, director of the Cancer Vaccine Institute at UW Medicine and a University of Washington and Fred Hutch Cancer Center faculty member, is on the verge of the greatest accomplishment of her 30-plus-year career: a breast cancer vaccine.

Last November in the medical journal JAMA Oncology, Disis and her team published the phase 1 trial results of a DNA vaccine targeting a protein known as human epidermal growth factor receptor 2, or HER2, produced in about 30 percent of breast cancers. Sixty-six women with advanced-stage metastatic breast cancer received the shot and were monitored for a median of 10 years. By the trial’s end, 80 percent of the participants were still alive—a colossal success considering only half of patients with similar stages of breast cancer survive after five years.

Enrollment for Disis’s larger, randomized controlled phase 2 trial is ongoing. If those results prove equally successful, “I think within the next decade, we will see vaccines as part of the standard of care of cancer treatment,” she says.

After three decades in breast cancer research, Dr. Nora Disis nears her medical moonshot.

Image: Courtesy Nora Disis

Some semantics: The HER2 vaccine isn’t the same as the types of jabs we get to prevent smallpox, polio, measles, even cervical cancer. The distinction is subtle. Disis’s shot teaches the body’s immune system to recognize and destroy breast cancer cells that express the protein HER2 to prevent them from emerging again—it doesn’t prevent a tumor from appearing in the first place.

It falls under the umbrella category of immunotherapy, harnessing the body’s immune response to fight against disease, especially cancer. And Seattle, in particular, is known for it. Disis moved here at the start of her career because “if you were interested in cancer and the immune system, this was really the place to be.” It still is, she says.

Previous advances in immunotherapy have already “changed the landscape of cancer treatment,” notes Dr. Shaveta Vinayak, CVI’s director of clinical trials and also a UW and Fred Hutch faculty member. Immune checkpoint inhibitors, for example, prevent cancer cells from evading the body’s natural defenses and are approved for use on over a dozen different types of cancer.

Cancer immunotherapy has been around for over a century, Disis says, dating back to William B. Coley, who, in 1891, injected bacteria into inoperable cancers in the hopes that the patient’s immune system would react appropriately. “We’re at a tipping point,” she says. “It’s taken some time to put the pieces together, but we’ve learned so much about immunotherapy and viral diseases that now people are moving from the laboratory into the clinic in a very rapid way.”

As Disis glimpses progress, she and the CVI team keep pushing. They’re developing vaccines to prevent breast cancer and colon cancer, and another to target cancer stem cells. One day, she says, she may finally be able to stop and bask in the success. “When you’re in the trenches, you don’t necessarily think about the impact every day, but it’s my life’s work. To see a vaccine get approved to become part of the standard of care for the treatment of cancer, I think that would just be mind-blowing.”